From soil to body: the link between the human microbiome and agriculture

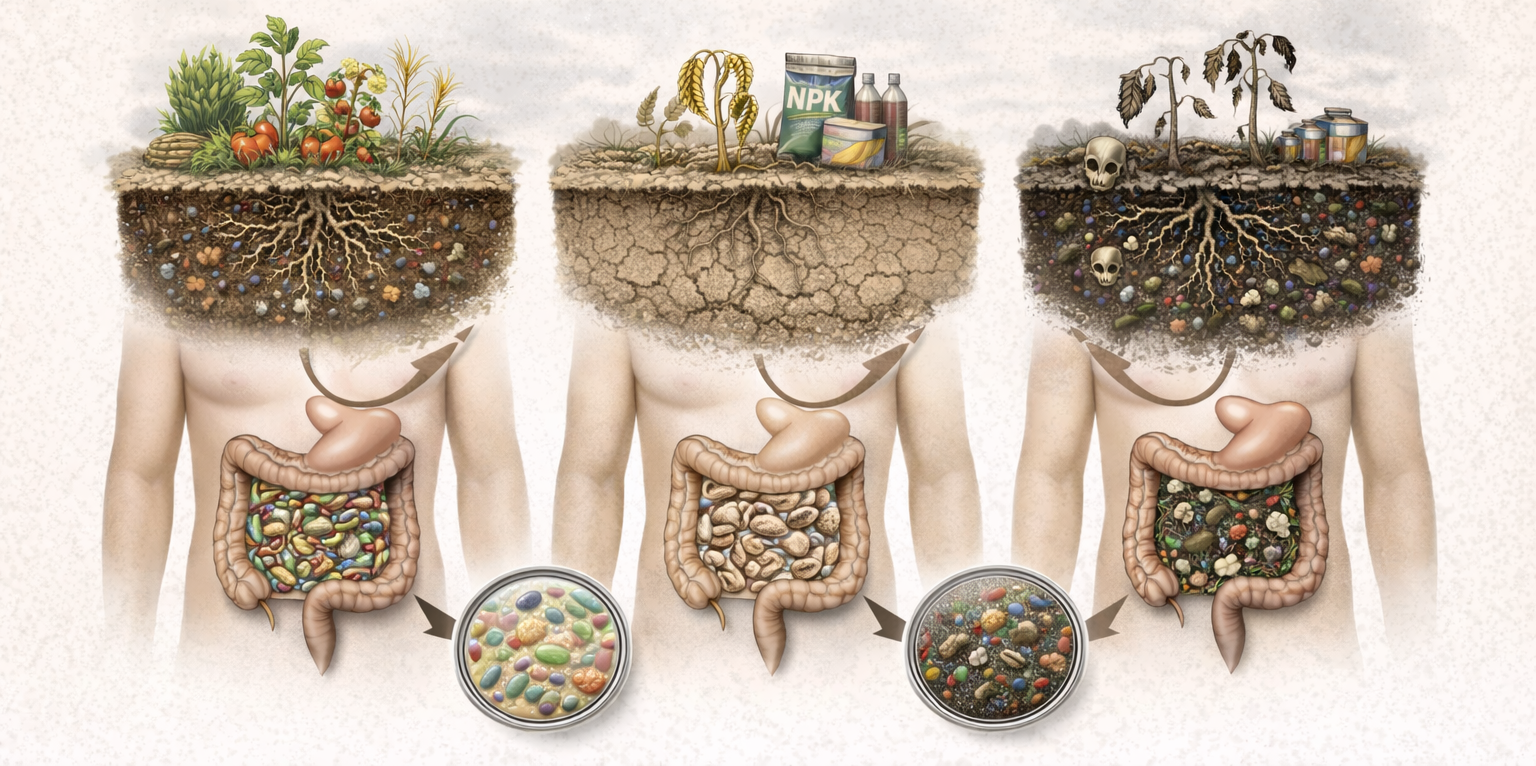

What links the fertility of a field to the health of our gut? What do soil microorganisms have in common with those that inhabit our bodies? And above all, what happens when the earth becomes impoverished and, with it, so do we?

The human microbiome is the collection of billions of microorganisms that live in our bodies and regulate fundamental functions: digestion, metabolism, the immune system and even neurochemical balance.

Surprisingly, the soil microbiome plays similar roles in the ecological sphere: it transforms organic matter, regenerates nutrients and supports plant health.

Scientific evidence shows that the biological quality of soil directly influences the composition of human microbiota through the food chain. The use of agrochemicals and the loss of microbial biodiversity alter not only soil fertility but also the balance of our internal ecosystem. Conversely, conscious agricultural practices promote microbial diversity and the transmission of nutrients and microorganisms that are beneficial to humans.

Therefore, understanding the link between the human microbiome and agriculture means rethinking health as part of an interconnected biological system that starts in the soil and extends to our bodies.

What is the microbiome: the microscopic universe inside and around us

The human microbiome is the collective genetic heritage of all the microorganisms that live in our bodies: bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc. These microbial communities populate the skin, mucous membranes, respiratory system and, above all, the gut, where over 70% of all microorganisms are concentrated.

Not to be confused with the gut microbiota, which represents the living component of these microorganisms; the microbiome describes the entirety of their genetic information. In short, the microbiota is “who lives in our body”, while the microbiome is “what they do” and “how they act” through their genes and metabolites.

The microbiome functions as a veritable biochemical network: a system capable of modulating thousands of metabolic signals, controlling nutrient availability and constantly communicating with host cells. This interaction is mediated by key metabolites such as fatty acids, biogenic amines and immunomodulatory molecules, which influence fundamental bodily functions and contribute to the stability of the entire bodily ecosystem.

Its structure is not static: the microbiome varies according to diet, environment, contaminants and the microbial quality of the soil from which food comes. Each individual hosts a unique configuration, a sort of “microbiological fingerprint” that reflects habits, territory and lifestyle. Maintaining this diversity is essential because ecosystems with high microbial variability are more resilient the more heterogeneous they are.

What if many eating disorders were not just the prelude to “illnesses”, but signs of an internal ecosystem in distress?

Some studies have shown that there are communication axes, such as the gut-brain or gut-skin axis, which function through nervous, endocrine and immune pathways. The microbiome participates in these exchanges by influencing inflammatory responses, psychological state and regenerative processes. Understanding this means, therefore, understanding a fundamental component of our physiology, which is much more dynamic and interactive than previously thought.

In addition to this biological, chemical and physical interpretation, researcher Alessandro Mendini has developed a more in-depth study that attributes the Earth's magnetic field with the primary force in the vital processes of soil, plants and the human organism.

Therefore, the biological properties of soil and organisms are not solely the result of chemical and microbiological processes.

Soil as the Earth's gut

The soil can be considered, to all intents and purposes, the planet's gut. In the soil, decomposers break down plant and animal residues, producing essential compounds such as humus and organic acids. These microbial processes determine soil fertility, regulate the availability of minerals and influence the ability of plants to absorb nutrients. Soil with high microbial activity — i.e. a rich and functional soil microbiome — is fertile, resilient and capable of natural regeneration.

Since the second half of the 20th century, the widespread use of herbicides, fungicides, insecticides and synthetic fertilisers has progressively altered this vital network. Chemical compounds reduce microbial biodiversity, inhibit humus formation and interfere with natural decomposition cycles. The result is poor or microbiologically sterile soil. The synthetic molecules used in modern agriculture are foreign to natural biological cycles, and therefore the soil microbiome does not “recognise” them and has no natural mechanisms for their degradation. As a result, these substances persist in the soil, accumulating over time and interfering with the activity of microorganisms.

Modern agricultural practices also contribute to the loss of microbial vitality: the progressive spread of monocultures is one of the main causes of biological impoverishment of the soil. Cultivating the same species over and over again reduces the ecological complexity of the soil. This results in a decrease in microbial biodiversity, with the loss of key functions in the decomposition of organic matter and in the regeneration and natural defence of plants. This impoverishment is transmitted throughout the agri-food chain: less diversity in the soil means less microbial diversity in food and, consequently, a more fragile and less resilient human microbiome.

At this point, can we still define the agricultural sector as “sustainable”? What are we really growing?

The human microbiome: how much does it depend on food and soil

What happens to our microbiota when we eat food grown in healthy soil compared to food grown in depleted, diseased or exhausted soil? And what is the impact of the chemical residues that food carries into our bodies?

Scientific literature highlights that the biological quality of the soil is reflected in the microbiological quality of food and, consequently, in the composition of the human microbiome. Plants grown in soil rich in beneficial microorganisms not only accumulate more bioavailable nutrients but also carry traces of symbiotic microflora capable of interacting with our own.

However, there is a downside: when the soil is contaminated, the relationship is reversed. Chemical residues from plant protection products and synthetic fertilisers do not remain confined to the field but reach our bodies through the food chain. Scientific studies on subjects exposed to agrochemicals show a reduction in intestinal microbial diversity, alterations in bacterial composition and changes in the metabolites produced.

For example, chronic exposure to organophosphate pesticides has been associated with changes in gut microbial metabolism in human populations. Another study has shown that “pesticide” residues in food are metabolised by the gut microbiota, affecting the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), molecules that are essential for the intestinal barrier and for modulating systemic inflammation.

All this raises an important question: is it possible to reverse the process, restoring vitality to the earth and, in turn, to the human body?

This question also gave rise to the work of the Research Department at AXS M31, the company that produces BioAksxter® depolluting bio-formulations: regenerating soils not only to obtain higher yields, but also to rebuild the agroecosystem compromised by pollution and restore the biological quality that nourishes the body.

In what we might call the ‘BioAksxter® perspective’, soil is not simply a productive substrate, but a living organism, an integral part of the planetary balance and human health. Regenerating the soil microbiome ultimately means regenerating the biological foundations of life.